Women’s Voices in Medieval Artes Dictandi and Model Letter Collections

date

1054-1155

author

title

M. virginali flosculo

bibliography

- Helene Wieruszowski, A Twelfth- Century “Ars dictaminis” in the Barberini Collection of the Vatican Library. Traditio 18 (1962): 382-393, in ead. Politics and Culture in medieval Spain and Italy, Roma: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura 1971, n. 14, p. 343.

- The ars dictaminis is transmitted in a single 12th-13th cent. manuscript (Ms. Barb. Lat. 47, fols. 24v-26r), which is preserved in the Fondo Barberiniani latini of the Vatican Apostolic Library. It presents stylistic similarities with the Silloge Veronese which is linked to the intellectual circle surrounding Magister Guido (cf. Magistri Guidoni Opera, ed. Elisabetta Bartoli, Firenze: SISMEL-Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2014, p. 48; Florian Hartmann, Ars dictaminis: Briefsteller und Verbale Kommunikation in den italienischen Stadtkommunen des 11. bis 13. Jahrhunderts, Ostfildern: J. Thorbecke Verlag, 2013, p. 124).

summary

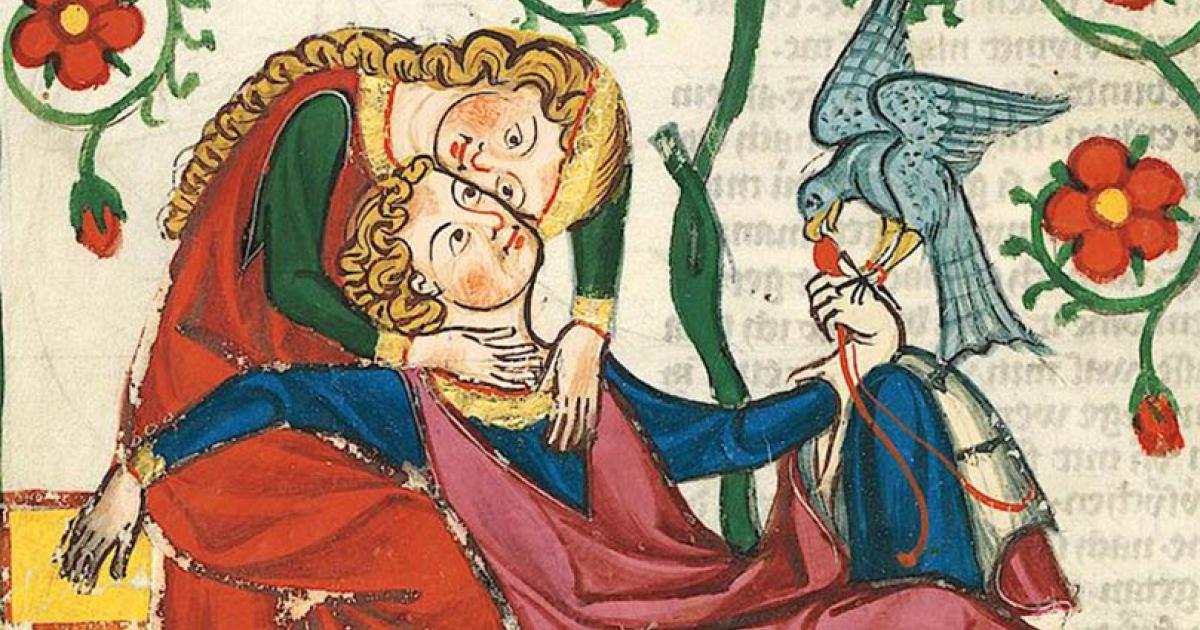

In the separation from his beloved the sender of the letter cannot find peace neither by day nor by night. The lover begs the woman to be able to talk to her and to taste her sweat candour.

The collection of eighteen model letters does not have rubrics, but rather marginal notes that tag each letter as M. (missiva) or R. (responsiva). Nine of the letters deal with ordinary matters of daily student life: requests of money and other objects such as a stylus and a writing tablet; parental admonitions on the conduct of the children; students’ reports on the progress of their studies, etc. One of them (8) explicitly refers to the study of ars dictandi and a few are about political Florentine affairs.

Women’s voices appear in the exchange of a couple of love model letters. The exordium of the missiva (14) of this correspondence plainly draws on Ovide. While the citation of Heroides, Ep. XII, 169 (non mihi grata dies, noctes vigilantur amarae) provides the topos of the lover weeping day and night, which appears either in Latin or in romance love literary traditions (e. g. Salutz d’amor). The allusion to the answer of Tiresias (Met., III, 316-338) offers a dictaminal reading of gender difference in sexual pleasure. The blind prophet in Greek mythology, who is a sexually variant figure that crosses gender lines, was asked by Zeus and Hera to adjudicate in their altercation whether women or men enjoy sex more. His answer, that women enjoy more than men, displeases Hera that blinds him.

Salutz d’amor. Edizione critica del ‘corpus’ occitanico, ed. Francesca Gambino, introduzione e nota al testo di Speranza Cerullo, Roma: Salerno Editrice, 2009, p. 85. For the reception of the story of Tiresias in the Middle Ages, see, among others: Jance Chance,

Medieval Mythography, Volume Two: From the School of Chartres to the Court at Avignon, 1177-1350, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2019, p. 166-167; Edward Wheatley,

Stumbling Blocks Before the Blind: Medieval Constructions of a Disability, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010, p. 131-132; Pernilla Myrne,

Female Sexuality in the Early Medieval Islamic World: Gender and Sex in Arabic Literature, London-New York-Oxford-New Delhi-Sidney: I.B.Tauris, 2020, p. 57-58.

Ars Barberini, nos. 14 and 15, p. 343

Ars Barberini, p. 332-333.

teibody

notes alpha

notes int